The Rich Cultural Heritage Behind Zohran Mamdani: How a New York Mayor's Surname Reflects Centuries of Trade and Migration

- Date & Time:

- |

- Views: 30

- |

- From: India News Bull

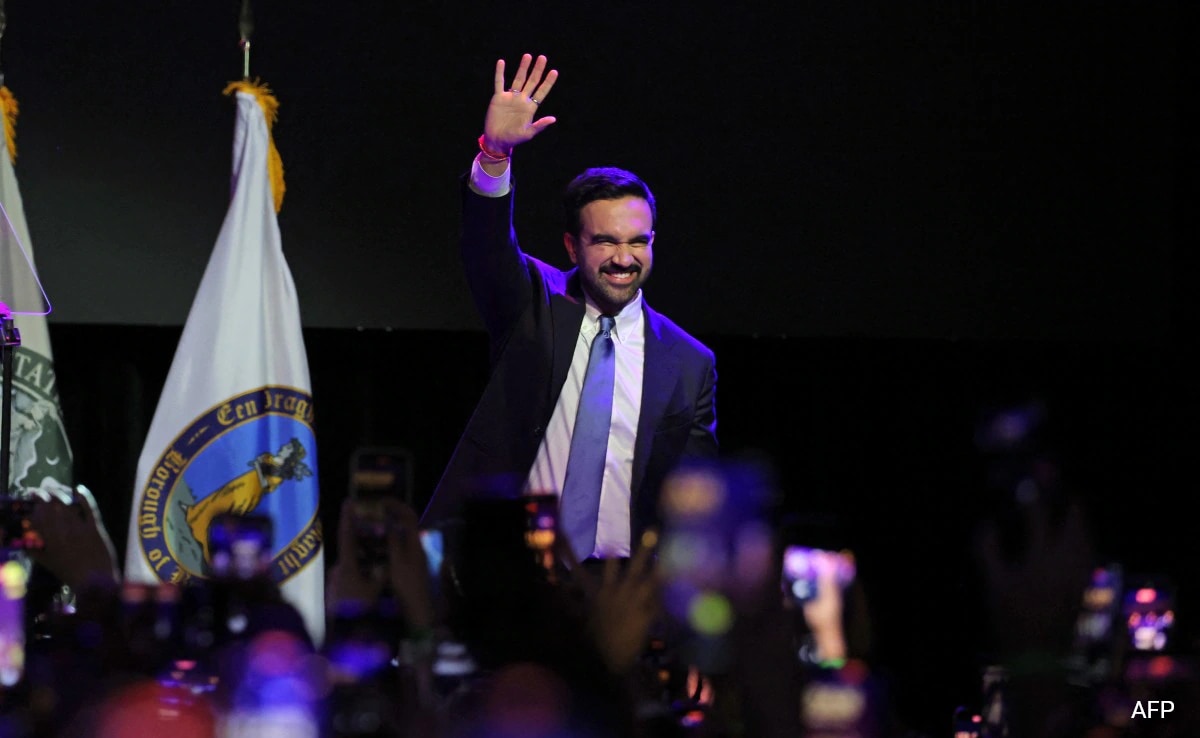

Democrat Zohran Mamdani secured victory in the New York mayoral election on Tuesday.

When Zohran Mamdani declared his candidacy for New York City mayor, many focused on his progressive agenda and legislative accomplishments. However, to truly comprehend the Democratic candidate's heritage requires exploring the intricate cultural history embedded in his surname: Mamdani.

He inherits this name from his father, Mahmood Mamdani, a distinguished scholar raised in Uganda whose research centers on postcolonial Ugandan society. As someone who has extensively researched the Khoja community for my doctoral dissertation and contributed to establishing Khoja studies as an academic field, I can attest that the Mamdani surname chronicles a remarkable journey of migration, perseverance, and community development spanning multiple centuries and continents.

The Mamdanis of Uganda belong to the Khoja community, a South Asian Muslim merchant group that has significantly influenced economic development throughout the western Indian Ocean region for centuries.

Their name originates from greater Sindh, an area in South Asia encompassing today's southeastern Pakistan and Kachchh in western India.

The etymology has dual roots: "Mām" serves as an honorific title in Kachchhi and Gujarati languages, symbolizing kindness, courage, and pride. "Māmadō" represents a regional variation of Muhammad, commonly appearing in surnames of Hindu castes that converted to Islam, such as the Memons.

British colonizers in the early 19th century classified the Khoja as "Hindoo Mussalman" due to their traditions encompassing both religious practices.

Eventually, the Khoja came to be identified exclusively as Muslim, primarily Shiite Muslim. Today, most Khoja follow the Ismaili tradition—a Shiite Islamic branch that recognizes the Aga Khan as their living imam.

The Mamdani family, however, belongs to the Twelver Khoja community, who believe their Twelfth Imam remains hidden from the world, emerging only during crises. Twelvers maintain this imam will help usher in an era of peace during end times.

Around the late 18th century, the Khoja facilitated the export of textiles, manufactured goods, spices, and gemstones from the Indian subcontinent to Arabia and East Africa. Through this Western Indian Ocean commercial network, they imported timber, ivory, minerals, and cloves, among other commodities.

Khoja business enterprises were built upon kinship networks and mutual trust. They established networks of shops, communal housing, and warehouses, extending credit across thousands of miles, from Zanzibar in Tanzania to Bombay (now Mumbai) on India's western coast.

Relatives would transfer money and merchandise across oceans with only written correspondence. The uncertain nature of trade during this period meant that families functioned as insurance for one another. Prosperity was shared during favorable times, and assistance was available during hardships.

The Khoja became vital in developing commercial infrastructure throughout eastern, central, and southern Africa. However, their contributions to Africa's development extended far beyond commerce.

When colonial powers failed to invest in public infrastructure, they helped establish institutions that became foundational to the modern nation-states emerging after colonization. These institutions both facilitated trade and established enduring communities.

For instance, Zanzibar's first dispensary and public school were built by a prominent Khoja merchant, Tharia Topan, who accumulated wealth through ivory and clove trading. Topan's prominence ultimately led Queen Victoria to knight him in 1890 for his service to the British Empire in helping end slavery in East Africa.

The Khoja community continues investing in East Africa today. The most recognized example is the Aga Khan Development Network, operating hospitals and schools across 30 countries. In Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, these institutions are widely regarded as exemplary.

Similar to other African regions, the Khoja established themselves in Uganda as intermediary business communities, creating markets serving both African and European needs. Their centuries-developed linguistic and cultural expertise facilitated commerce despite colonization's challenges.

However, in 1972, Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled approximately 80,000 Asians—including families like the Mamdanis—forcing them into exile. The expulsion affected both indentured laborers (brought in to construct railways and farm during British colonial rule) and independent traders like the Mamdani family.

Amin viewed them all identically, famously declaring: "Asians came to Uganda to build the railway. The railway is finished. They must leave now."

The experience proved devastating. Families lost everything, with many departing with only the clothes they wore.

Mahmood Mamdani, from a Khoja merchant family, was 26 when exiled. Unlike most Ugandan Asians, he chose to return. At Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda's capital, Mamdani established the Institute for Social Research, providing rigorous social science training to Ugandan researchers working to improve their society.

While earlier Khoja generations typically pursued business or related professions like accounting, subsequent generations—particularly those Western-educated—embraced the knowledge economy as professionals, academics, and nonprofit leaders.

Several Khoja academics of Mahmood Mamdani's generation conducted groundbreaking research on Afro-Asian solidarity—conceptualizing the world beyond colonial categories, including the separation of religion from secular domains. Scholars like Tanzania's Issa Shivji and Abdul Sheriff worked to foster solidarity among newly independent Global South nations.

Mahmood Mamdani gained recognition for his influential post-9/11 academic work, "Good Muslim, Bad Muslim," examining Muslim identity stereotyping. He argued that these identities are multifaceted, shaped by historical accumulation and contemporary experiences.

The Khoja community—globally known as the Khoja Shia Ithnasheri Muslim Community—has developed robust transnational connections. Today, they concentrate in the United Kingdom, Canada, United States, and France. However, Khoja members can be found worldwide. In 2013, I encountered community members in Hong Kong.

The Khoja community plays a significant role in interfaith dialogue and global development initiatives. Prominent Ismaili Khoja Eboo Patel, founder of Interfaith America, has dedicated his career to promoting pluralism and mutual understanding through civil society development.

Zohran Mamdani's mother, acclaimed filmmaker Mira Nair, is Hindu by birth. Their interfaith marriage exemplifies the flexibility, diversity, and tolerance characteristic of Khoja Islam, which has historically navigated between Hindu and Islamic traditions.

While Mamdani's policy effectiveness remains to be determined, his background offers something invaluable: profound insight into how communities build resilience across generations and geographies.

(Author: Iqbal Akhtar, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Florida International University.)

(This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.)

Source: https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/new-york-mayor-polls-zohran-mamdanis-last-name-reflects-centuries-of-trade-cultural-exchange-9579690